Ryukoku University You, Unlimited

Need Help?

Criminology Research Center(CrimRC)

Highlights of Research Findings

Research Unit for Therapeutic Jurisprudence

This unit attributes crime and delinquency to “isolation” from people and society. Desistance is a very important topic in criminology. We not only work with researchers and practitioners to understand the causes of crime and delinquency, but also conduct joint research with stakeholder groups. The Therapeutic Jurisprudence Unit has pursued unique initiatives with stakeholders such as the Drug Addiction Rehabilitation Center (DARC), which is an organization that assists recovering drug addicts, non-profit organizations that help inmates and ex-offenders released from prison, and families and supporters of inmates and ex-offenders. We bring together these stakeholder groups along with community residents, welfare service professionals, public officials, and other people active in a variety of roles and provide a forum to share issues. Modeled on round table talks, this method is called “ENTAKU” and has been applied in various locations and used to address a wide range of issues.

Many different factors are behind crime and delinquency, including a difficult upbringing, poor education, and personal illness or disability, as well as lifestyle problems such as poverty and dependency on drugs or alcohol. People faced with difficult lives have trouble overcoming these types of challenges under their own power. For example, Japan has adopted a strictly punitive approach to users of illegal drugs. While many parts of the world are looking to decriminalize cannabis and other drugs, Japan is preparing legislation that will even penalize personal cannabis use, an act that previously went unpunished in Japan. Criminal punishment creates stigma that has serious consequences for the individual. Drug users need proper support that is focused on harm reduction and not social stigma.

To advocate for this approach, Ethan A. Nadelmann was invited to an international symposium held on the topic of “harm reduction” where this idea was promoted to the wider public. Alongside an expert council on drug policy organized by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, we organized an open workshop with experts, practitioners, and concerned parties acting as rapporteurs who reviewed the expert council’s discussion and improved their understanding of cannabis.

The “Experts’ Seminar Drug Addiction Recovery Supports in East Asia 2019” was also held to explore collaboration with researchers and supporters in East Asia, where drug policy tends to be more punitive. These efforts at international coordination and collaborative research have produced results such as the JSPS Bilateral Program Joint Research and Seminar “A Comparative Study on Policy, Law and Enforcement of Narcotic Drug: Cross-National between Thailand and Japan (2022)”, and we hope to continue and expand on these efforts.

Research Unit for Forensic Methodologies

This unit addresses issues in Japanese criminal law re garding the topic of scientific expert testimony.

In many cases, the rights of suspects and defendants are not fully protected in Japan. This is due to a culture that requires punishment and secrecy, and above all, the overwhelming disparity in personnel and fiscal resources between lawyers and investigators. Expert testimony in court is emblematic of this problem.

In Japan, various initiatives have been organized to protect women and children from domestic and child abuse. One of these is giving public authorities the ability to actively intervene in family affairs. Recent reports have shown a sudden increase in child abuse cases in Japan, but some cast doubt on these findings. Bringing the legal system to bear on family affairs has brought external interventions and checks to the previously private sphere of the family. Some experts believe this has unearthed abuse cases that previously went unreported, causing the increase in cases. What is certain is that aggressive intervention in the home is leading to wrongful convictions.

The story behind shaken baby syndrome (SBS or abusive head trauma: ABT) is an interesting example. SBS was first described by an American pediatrician in the 1970s who proposed a diagnostic triad of retinal hemorrhage, cerebral edema, and subdural hematoma was caused by violent shaking in children. Based on this theory, when Japanese doctors now observe these three signs of SBS, they are required to report it to the police. Parents can face criminal trial because of this reporting. However, questions were raised in the 1990s on the reliability of this diagnosis. In 2014, the Swedish supreme court even reversed a related conviction citing that the theory lacked credibility. The Innocence Project in the U.S. has also dealt with a large number of cases of wrongful convictions related to SBS. The issue with SBS is that abuse is determined solely on the bases of diagnostic criteria that are indefinite and lack credibility, thus resulting in wrongful convictions and unnecessary separations of children from their parents.

Demonstrating any theory requires a variety of different evidence. Judges render their decisions based on the evidence they are presented, but evidence is not easily verified in Japanese criminal trials. As mentioned earlier, there is a massive disparity in the personnel and fiscal resources available to individual lawyers and public prosecutors working for the country. So what kind of assistance is needed in situations where judicial outcomes rest on highly technical expertise?

The Research Unit for Forensic Methodologies has gathered experts involved in expert testimony at criminal trial and is working to establish a knowledge-sharing network on the topic. The unit has collaborated with researchers, lawyers, doctors, and medical examiners to conduct a series of overseas investigations and workshops that look at trials involving SBS in Japan. Foreign experts have been invited to Japan to participate in multiple international symposiums to address this issue on a broader scale. As a result, in Japan, where conviction rates for criminal trials are high, judgments based solely on SBS theory are gradually undergoing reexamination and wrongful conviction rulings are now being issued.

Nevertheless, there are still many cases of suspected wrongful convictions in Japan, and the unit will continue working across professional and disciplinary boundaries to address this problem in unison and change the unfair criminal justice system.

Evaluating and Proposing Policies on Crime

Professor Koichi Hamai of the Policy Evaluation Research Unit participates as an expert in the Japanese Ministry of Justice’s Model Project for Regional Recidivism Prevention and in plans for recidivism prevention formulated by local governments.

Professor Hamai noted, “Unfortunately, criminal policy is often only discussed in Japan immediately after a serious and unusual event. In other words, in a country with very low levels of crime like Japan, criminal punishment does not receive the scrutiny it deserves because the government only takes action when there is uproar in mass media and general society in response to an unusual incident.”

CrimRC hopes there will be a shift in society that allows policymakers, practitioners, and citizens to engage in discussions about evidence-based policy (EBP). Many overseas researchers have been invited to CrimRC workshops that are open to the wider public. Some of these researchers are introduced below.

|

Prof. Dr. David Weisburd (Visited in May 2018/Related Page) Under the topic of “The Importance and Practice of Evidence-Based Measures against Crime,” views were exchanged on the effectiveness and need for evidence in policy while police activities were compared between the U.S. and Japan. Dr. Weisburd introduced research methods and case studies that attracted the interest of Japanese researchers and practitioners. |

|

Prof. Dr. Lorraine Mazerolle (Visited in February 2019/Related Page) The work of the Campbell Collaboration, which has an international network, was introduced. Views were exchanged on how to generate high quality evidence and the significance of allowing open access to it. Prof. Mazerolle’s statement “The core idea behind this project is to cause no harm. That is, judicial intervention in crime (by police, courts, correctional institutions, etc.) should not be harmful. We must aim to intervene in ways that reduce crime but also do not harm society,” provided important food for thought for policy planning. |

|

Prof. em. Dr. Frieder Dünkel (Visited in November 2019/Related Page) In 2022, Japan revised its age of legal adulthood from 20 to 18 following amendments to the Public Offices Election Act and the Civil Code. A debate ensued as to whether the age of applicability of the Juvenile Act should also be lowered to under 18 years. Prof. Dünkel stated, “The Council of Europe and the European Union emphasize improving protections for the legal rights of juveniles in criminal proceedings. Europe is even extending the scope of juvenile justice to include young people who are 21 years or even older. Based on evidence from neurological science that the brain fully matures at around 25 years of age, it seems reasonable that people should bear full criminal responsibility from a more mature age, such as 21 or 25 years.” Unfortunately, juveniles 18 and older who commit serious crimes in Japan are currently tried under the same system as adults. We must continue to carefully monitor the effects of this policy on society. |

|

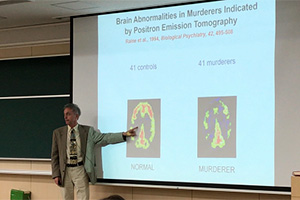

Prof. Dr. Adrian Raine (Visited in October 2017/Related Page) Prof. Raine gave a lecture about how violent personalities are formed by biological factors such as the brain, genetics, and nutritional status, as well as by interaction between biological factors and societal factors such as the environment in upbringing (biosocial perspective). An important role of CrimRC is to share new findings based on this type of medical evidence in addition to sociological and statistical evidence. |

International Exchange and Communication

CrimRC actively engages in academic exchange with overseas universities and research institutions and takes on overseas researchers as contract researchers.

For example, presided over by the Delegation of the European Union to Japan, CrimRC obtained a grant from the International Credit Mobility program of Erasmus+ (the EU’s new program to support education) and in 2018 concluded an arrangement for student and faculty exchanges between Cardiff University and Ryukoku University. In April 2019, Prof. Trevor Jones and Dr. Adam Edwards visited Japan from Cardiff University to exchange perspectives on criminology education and criminological theory in UK and Japan.

CrimRC has also been raising crime-related social issues from a broader standpoint.

In June 2018, a symposium titled “The U.S.-Japan Joint Teach-in: The Japanese Constitution and the Death Penalty: Do Executions Performed during an Ongoing Request for Retrial Violate the Constitution?” was held in two locations, Kyoto and Tokyo. Prof. Dr. Carol S. Steiker and Prof. Dr. Jordan M Steiker, lawyers involved in the Innocence Project, were invited from the U.S. for the symposium. Professor Shinichi Ishizuka, who has advocated for abolition of the death penalty in Japan and overseas in the course of his research and legal practice, played a central role in the event. Professor Ishizuka also recently participated in the “Life Imprisonment in Asia: Law and Practice” Online Conference (2021), an international conference that discussed life sentences in Asia that was organized by the School of Law, University of Nottingham in the UK and by the School of Law, Vietnam National University Hanoi.

Professor Kim Sangyun is tackling the issue of hate crimes against social minorities, researching the issue in Japan but also incorporating events from outside Japan, such as hate crimes against Turkish immigrants in Germany, and is actively promoting initiatives to eliminate discrimination.

In 2021 and 2022, journalist Mika Funakoshi, a research member, led several workshops on the topic of crime during war and in conflict zones. Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a victim of torture at the hand of the U.S. in Guantanamo Bay detention camp, was invited and interviewed, and a report was presented on the violence perpetrated against citizens by the military regime in Myanmar.